Rashod Taylor

Well, first of all, this interview is a reposting of the one I had done initially over at Analog Forever Magazine last year. The end of this is slightly updated to reflect on some recent accomplishments and changes in direction. However, still, a great reflection of the work, process, and man that photographer Rashod Taylor has been and continues to be. It's from here that I get to look back, not that long ago, and witness the determination and progress of someone who approaches his work, professional, and family life with love, compassion, and kindness.

It's a lot to take care of over in the Taylor camp, that is for sure. The man has his hands full. Thankfully, I got to him reasonably early and reached out as a fellow visual artist with some opportunities and ideas. He was more than forthcoming with interest in collaboration, and it is with great pride that I can say we've worked together on a few things that have brought some light and opportunities to others as well — certainly a win-win for both of us. I don't know how he finds the time, but I'm willing to bet that he has some friends and family that are behind him 100%. It takes a village, right?

I'm kind of just blathering on with no real point or direction except to say that Rashod Taylor continues to be the type of person we all need to be. Positive, kind, and hardworking. He's not one to sit back and tell people on social media how much he has done, how far he has gone, or how vital his opinions are to everyone. He simply gets out there, does the work, meets the people, and reaps the personal and professional rewards. Case in point is the main focus of the interview – his body of work, Little Black Boy. This work hit me hard when I first saw the photographs – as it opened my eyes a bit more than before and made me feel what it is that Rashod feels. Hell, I still feel it, and I'm better for it. Trust me, you'll see. I'm also better for just knowing the man – a real, tangible change. So my hope is that in reposting this interview, more people will get to see the work and process of someone who might help you experience a tangible change in your life. It doesn't matter in what manner it happens, just so long as you recognize it when it hits. So read on, and glean something worthwhile.

Untitled #2, 2020, from Little Black Boy

Bio -

Rashod Taylor is a fine art and portrait photographer whose work addresses themes of family, culture, legacy, and the black experience. He attended Murray State University and received a Bachelor's degree in Art with a specialization in Fine Art Photography. Since then, Rashod has exhibited and published his work across the United States and internationally. Most recently he has exhibited his work as part of the group show, Reflecting Voices at the Colorado Photographic Arts Center in Denver, CO. He is a 2020 Critical Mass Top 50 Finalist, winner of Lens Culture’s Critics Choice award, and a 2021 Feature Shoot Emerging Photography Awards winner. Rashod’s clients include National Geographic, The Atlantic, Essence Magazine, and Buzzfeed News. His work has also been featured in Feature Shoot and Lenscratch among others. He is currently working on a series called Little Black Boy, where he documents his son’s life while examining the Black American experience and fatherhood. He lives in Bloomington, IL, with his wife and son.

Interview -

Michael Kirchoff: Every photographer experiences that spark that drives them into the direction of image-making. How did you get your start, and what were your early influences?

Rashod Taylor: When I think about experiences that have pointed me towards photography I tend to go back to when I was around 8 years old and being very interested in our family albums. We would have boxes full of photos and albums that my mom would put together. Growing up my parents would take photos for all our events, birthdays, vacations, and family gatherings with this little 35mm Vivitar PS:35 point and shoot. I remember that little camera till this day. It’s probably sitting in a box somewhere at my parent’s house. Those memories have stuck with me and really sparked my interest in photography. I continued to get more into photography in high school working at the school newspaper and yearbook covering events and making portraits. Ever since then I gravitated to photographing people and that has stuck with me ever since.

MK: What does a typical creative day consist of for you? Do you consider yourself a workaholic, or do you keep a schedule of time for family, socializing, vacation, etc?

RT: I have a day job so photography is done outside of that and forces me to have a schedule. Since most of my photography is of my family and friends I bring my camera with me to most places. However, with COVID I am working from home so I have my camera set up and at the ready. While I always try to be ready to make a picture most times I plan out when I will make pictures. What takes the most time for me is the developing, printing, and scanning. I have spent many early mornings and late nights in my darkroom working. The weekend is where I get the most done with photography and it’s typically in the morning. I hang out with the family later in the day and at night. Photography has been such a big part of my life, having my camera with me is just second nature at this point. As of late, I have been in the mode of just putting my head down and making work. So from that standpoint, I guess I could be considered a workaholic. If you ask my wife she would probably confirm that and tell you that my darkroom is my side chick.

MK: That’s hilarious! Well, at least it sounds like you won’t get into too much trouble, being that it’s your artistic outlet. What about other artistic mediums that inform your work and process? Music? Film? Literature?

RT: I would say literature in regards to history. I am very interested in how history shapes cultures, ideas, and the way we live today. More specifically African American history as I pull from that in my work. I like to use history as a bridge to inform my work and also give context. I recently visited Washington D.C. to explore the National Museum of African American History and Culture. It was an amazing experience and quite emotional. Ultimately it was so gratifying to see a building that acknowledges that my history is not only black history but American history. There is this sense of validation that comes with visiting a place like this, to have on display blackness in its truest form. From the unimaginable hardships and struggles to the joys and triumphs. Going through the museum and seeing and reading all of the history deeply resonated with me and gives me additional perspective as I continue to make work.

LJ Standing in the Backyard, 2020, from Little Black Boy

Bath Time, 2020, from Little Black Boy

Best Buds, 2019, from Little Black Boy

Deep Sleep, 2020, from Little Black Boy

MK: How has your photographic education, no matter where it has come from, informed your work? Or perhaps it is simply a matter of having a hands-on approach to moving forward with your imagery. Does formal education supersede real-life experience?

RT: I would say that my photographic education has informed my work. I graduated from Murray State University, which is located in Murray, Kentucky. Earning an art degree helped me with a foundational understanding of making artwork and developing a visual language to communicate intent and meaning. For me, the education system gave me a playing ground to experiment and figure out what I liked and didn’t like. At the same time, it helped me start to find my voice and figure out what I wanted to say with my work and how I wanted to say it. On the flip side, I don’t think formal education supersedes real-life experience in most cases. You can know all of the art history; have tons of art speak but not make good work. Ultimately it comes down to making strong work that can inspire and connect with people. That is what really matters. After school I would say I developed even more as an artist because I sought out my own education in different topics and history that I was interested in and used that to help inform my work. In addition just plain old life experience I think informs work also. A lot of my work is a response to where I am in life and depicts that in imagery.

MK: Do you find it better to construct your images in a mindful way or work more intuitively? In the case of Little Black Boy, are you simply reacting to moments as they occur?

RT: I do both in my work. In the case of Little Black Boy, I like to construct my images with a specific goal in mind, controlling as much as I can in the frame to say something. It may be a loose idea or something specific that I want an image to express. Shooting 4x5 helps with that because it slows me down to contemplate and take everything into account on the ground glass. On the other hand, some of my images in that series are more reacting to the moment. Well as much reacting to the moment as you can when shooting large format. For instance, the image of LJ and my wife in the bathtub was in the moment. I was busy doing something and my wife kept calling for me to make a picture of them. Once I finally got in there and saw the positioning I thought oh wow I need to hurry up and capture this. My wife is a big help with the production of my photographs with this series; she is oftentimes helping me get our son in the correct position and doubling as my photo assistant.

MK: You have been receiving some well-deserved recognition for your series Little Black Boy. The more I see it come up, the more impressed I am with how you have addressed fears and concerns within the Black community. There is a very tangible understanding of the emotional toll that occurs from the perspective of family. Maybe this is a good time for you to address the “why” within this work. And please let me reiterate that I think this is a body of work that truly sets a tone easily understood across the racial spectrum.

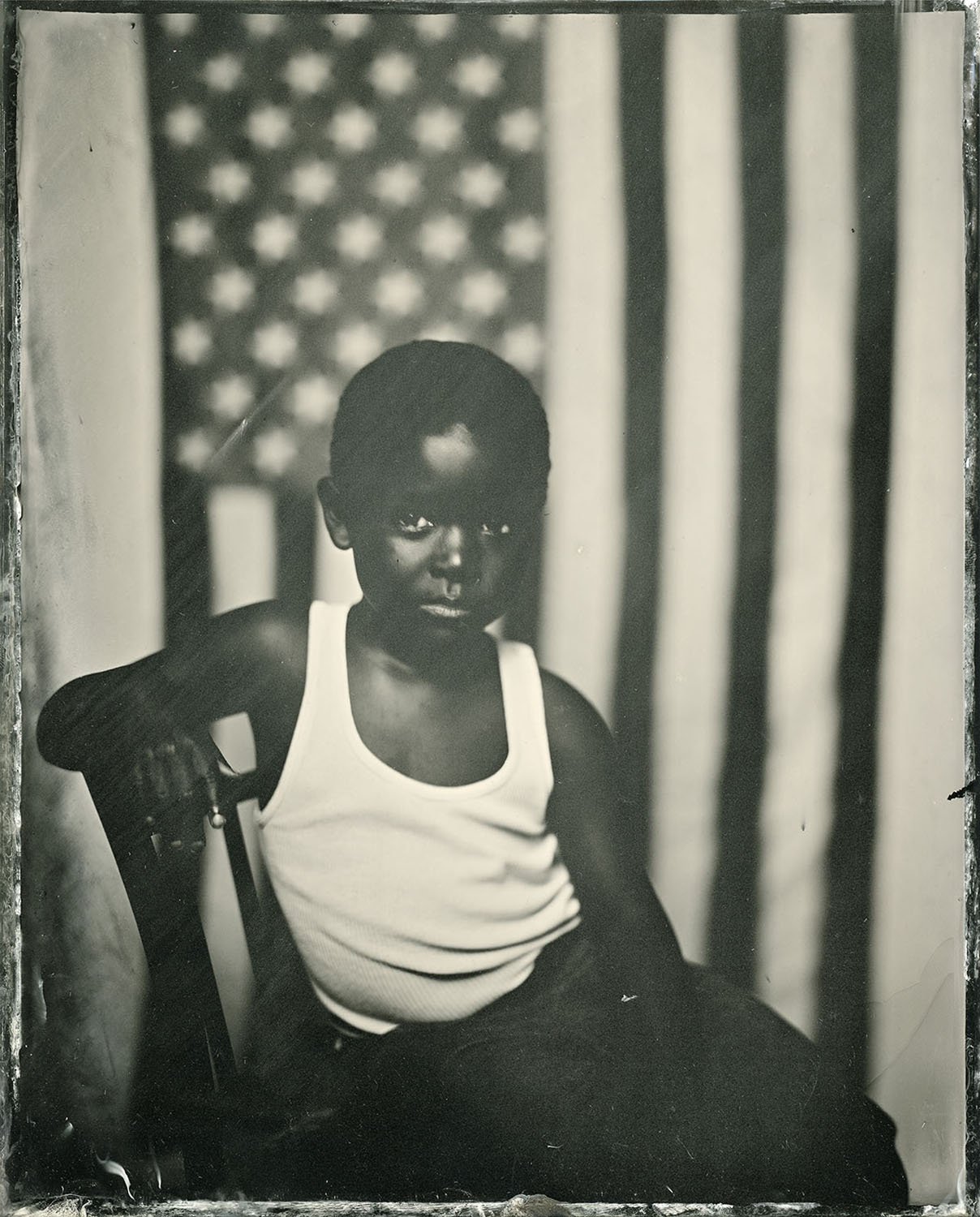

RT: Thank you, this project started to simply document my son’s life but as I photographed him more I started to see themes within the images that I wanted to address more intentionally. I wanted the viewer to see what childhood is like growing up black in America and also the viewpoint from me navigating fatherhood as a black man trying to get over fears and insecurities while leading my son through his childhood. All of this while displaying the realities of racial inequality and social injustice that are prevalent in our lives. With these different themes in mind I work to package this work in a way that it can show love and tenderness but at the same time highlight the pain and struggles that we go through as people of color. With the work, I give it a sense of duality where one image can be read multiple ways. This I think is where the images have the ability to connect and do so with different audiences. Ultimately, I want to keep the conversation going in terms of the black experience and elevate the depiction of black life which has been very much one-sided by media and in the consciousness of America. I see many possibilities for my son, and I want these images not only to capture who he is and what he can accomplish but show that black children have bright futures and can make an impact despite having a handicap that other children simply don’t have based on the color of their skin.

Hiding, 2019, from Little Black Boy

LJ and his Fort, 2020, from Little Black Boy

LJ and Marianne Sleeping, 2020, from Little Black Boy

LJ Sitting on Bench, 2020, from Little Black Boy

Papi’s Hat, 2020, from Little Black Boy

MK: What is the long-term goal for this project?

RT: My goals and why for the project are intertwined. I want to give the viewer a different perspective, I want them to gain something or connect to the work in a way they didn’t think they could. In addition, keeping the conversation going in terms of race, equity, and representation for Black Americans is an important goal also. From a more concrete perspective, I desire to publish a book on the series and would want to exhibit the work and get it into collections. I do have some time as I will be shooting this project for the next several years.

MK: I can definitely see this as a book project, and taking your time seems like a sensible route to go. Do you think there is one image that stands out as a signature photograph or one that speaks loudest? Why?

RT: I would say the image titled “Deep Sleep” speaks the loudest for me because of the personal meaning that it carries with it. I wanted to make that image for so long and struggled to make it There was the logistics of getting a four-year-old to do exactly what you want with large format and secondly me facing my own insecurities. In my mind, this image has a duality that I strive to be present in this work. On one hand, it shows youthfulness, beauty, and peacefulness but on the other side, it really shows this post-mortem look of my son. It embodies one of my greatest fears. It speaks to the fragility and vulnerability of being a black father and having the possibility of your child being killed by outside forces whether that be police or people who have a hatred for you because of the color of your skin. So this one scares me to death but I needed to face these realities and my own insecurities, which I do through this body of work.

MK: Is there work by another artist that you are currently paying attention to more than anything else? Does the work of others inspire you to go out and create?

RT: I have always been really into Sally Mann and go back to her early work with immediate family often. It’s just amazing work that I feel will always be relevant to me. She is an artist that showed the art world that photographing your kids is art and should be held in that esteem. I also go back to this quote of hers, “the things that are close to you are the things you can photograph the best. And unless you photography what you love, you are not going to make good art” In the same breath I would say Gordon Parks, Roy DeCarava, Carrie Mae Weems and Dawoud Bey are photographers that have played a part in shaping my work and the way I look at photography. While I can agree that the works of others inspire me and informs my work. However, what inspires me to create goes back to this deep desire to bring meaning and significance to the time I have on earth. For me, photography has the ability to bring awareness and support change. I want the themes in my work to resonate with people long after I am gone. I think of the power that photography holds. I go back to Fredrick Douglas who was the most photographed person in the 19th century. He wanted to be photographed extensively so he could show America images of blackness that contradicted racist stereotypes of the times. This idea really encompasses my feelings on the why behind getting out and making images. I want to leave a record of blackness that is not mainstream in hopes that people can see and be inspired by positive images of black life.

Self-Portrait with LJ, 2020, from Little Black Boy

Standing in my parents backyard, 2020, from Little Black Boy

Superman, 2019, from Little Black Boy

Tired of Fighting, 2019, from Little Black Boy

MK: Is there anything that surprises you about the visual marketplace and how it operates? Anything that you think might need changing?

RT: I don’t know if much has surprised me when it comes to the visual marketplace. However in looking at the art world and institutions, which historically have not had a great track record in representing people of color and valuing their work. There is a lot of work that needs to be done on that space. With the climate right now in terms of race and social justice, I think I think that some institutions are taking notice and looking at their practices, which is a step in the right direction.

MK: I would completely agree, and my hope is that this change for the better continues with the help of artists like yourself.

Let’s take a look at how you make your images. Are there specific tools you feel are best in order for you to create? How do they apply to the work in making the best photograph you can achieve with the overall intention you’re looking for?

RT: Yes, I’m ready to nerd out! Film will always hold a special place in my heart and it’s an essential tool for my art-making. It slows me down, the depth and quality of the images it produces have a look that I love. I have photographed using formats from 35mm to 8x10 and feel that different formats help bring your images to life in different ways. As of the last few years, I have settled on shooting 4x5. While I will shoot 8x10 for wet plate, 4x5 is the sweet spot for me between portability and cost. Photographing this way is a meditative process for me and it allows the sitters to relax. Large format helps me focus on composition, light, and image construction. With the constraints on spontaneity that comes with photographing this way, it forces me to bring a higher level of visualization to the image-making process. Lastly the size of the negatives and image quality is amazing and it allows me to make big prints. Film brings permanence and softness that I want in my work.

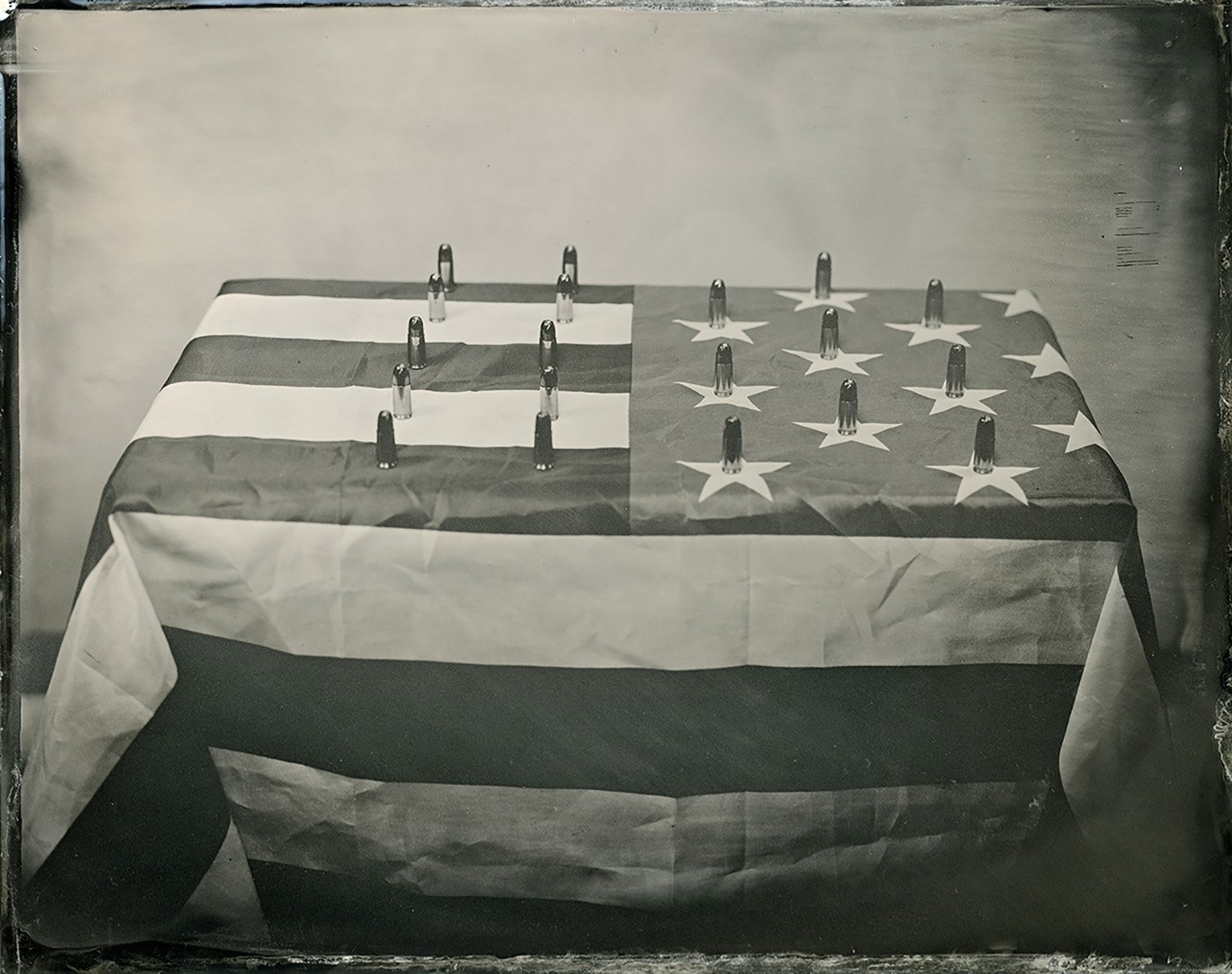

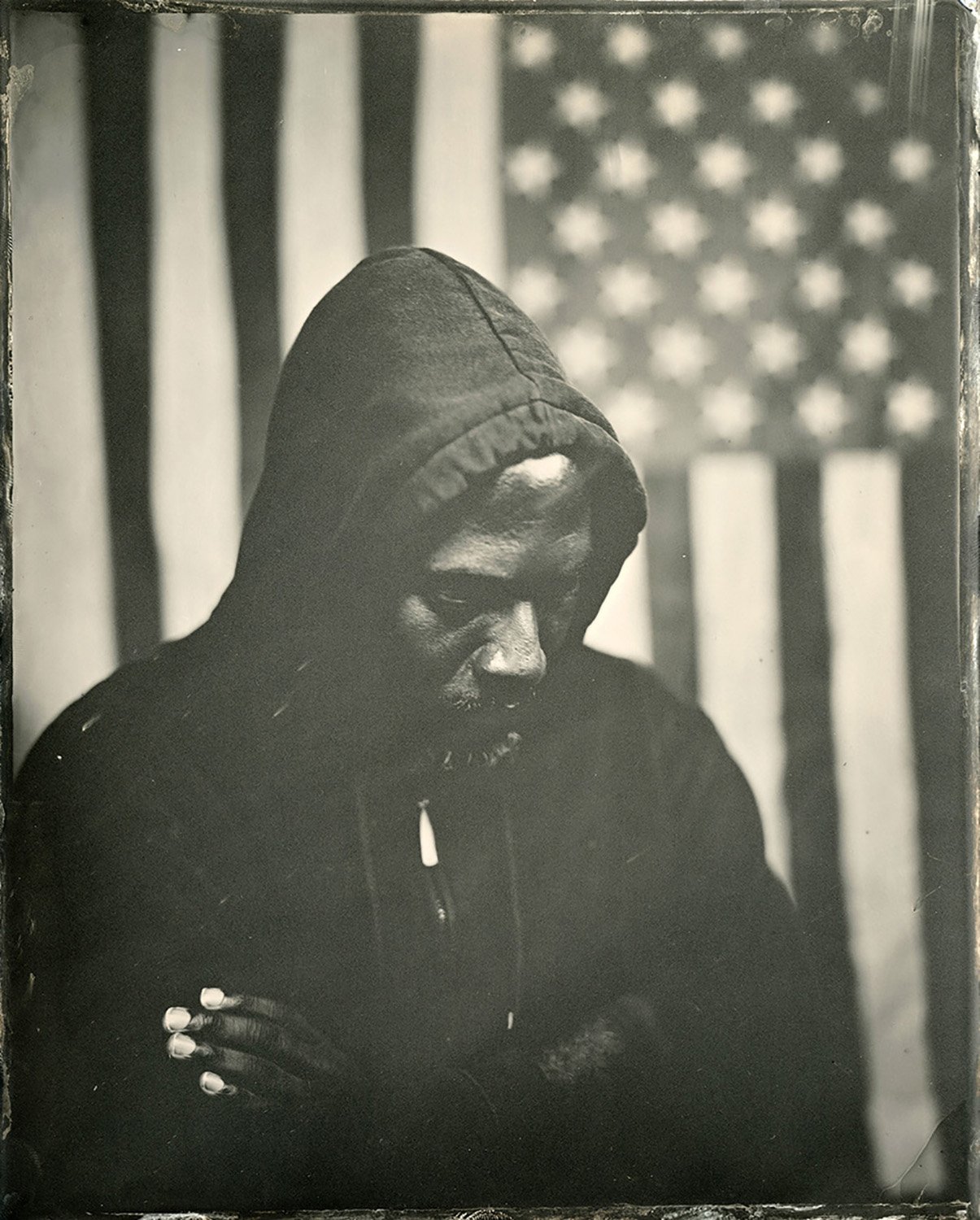

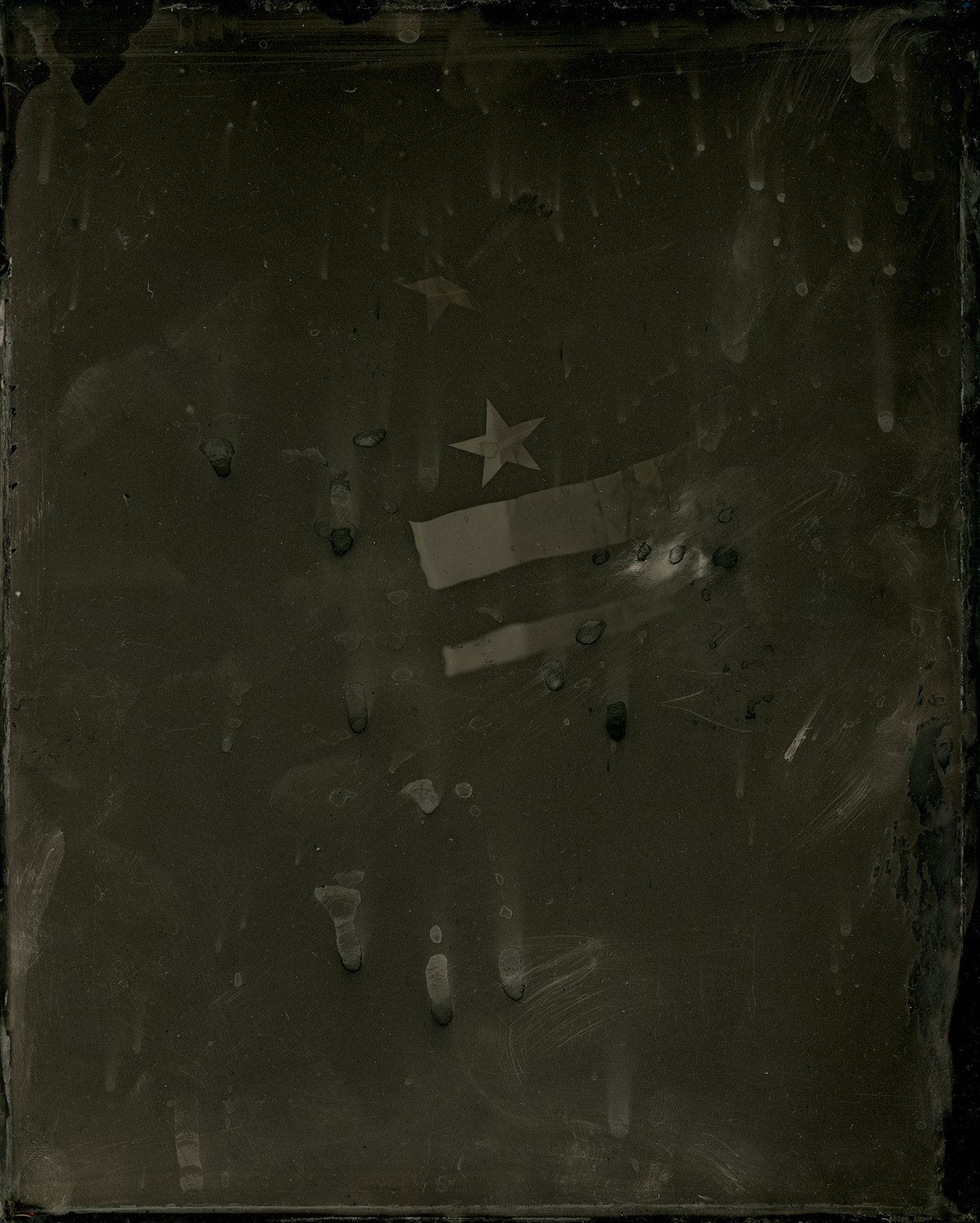

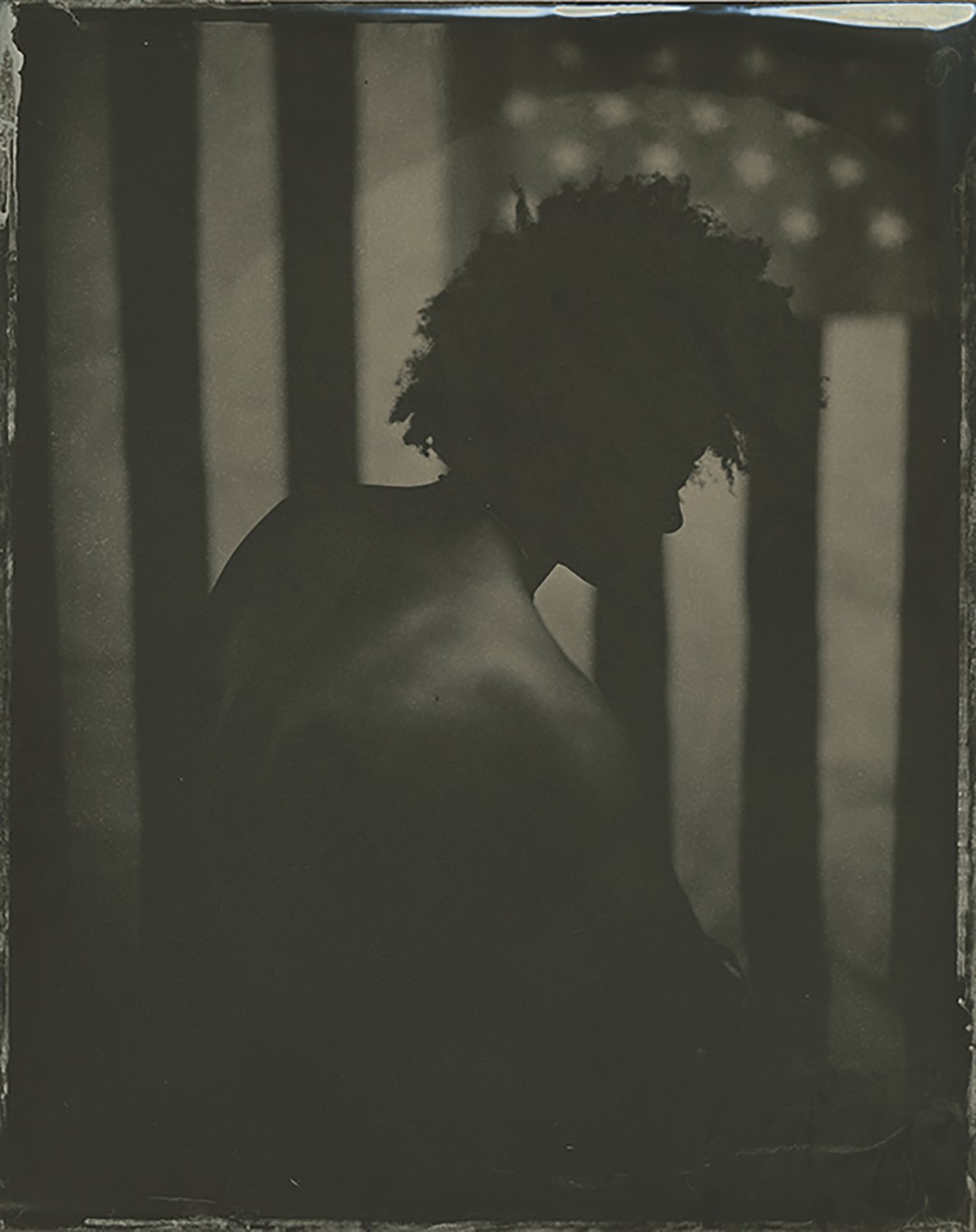

MK: I notice that you have also been working with the wet plate collodion process, most notably with the short series, My America. So with the proliferation of digital technology taking over the photography world, there seems to be some pushback from the analog world. We are beginning to see a trend of more and more photographers taking on historical processes. Do you feel this is exactly that, a trend, or that possibly people have a deeper desire to return to the way we used to make photographs before the pixel took over?

RT: I think it’s more than a trend. These days everyone (me included) has thousands of images between phones, hard drives, and cloud storage. Most of these will never see the light of day that exists outside of posting on social media. Getting back to making images that you can hold in your hand and that will last will always have a place. There are people who have spearheaded this resurgence like the wet plate OG John Coffer who has been doing this stuff since the 1980s. This process is something that people have embraced and it’s becoming more and more popular. For me, I have a deep desire for permanence and longevity with my work, which is partly why I shoot with the process. Tintypes and ambrotypes from the civil war era are still around; while there are no guarantees that a fine art print will last 100 years.

My America

MK: I know you have one foot in the commercial photography world and the other in the fine art arena. Do you see a difference between how you approach your personal work versus the images you create for others or do you feel they inform and inspire one another?

RT: Right now yes, I approach commercial work differently. But I am always striving to keep the two as close as possible. I want both to connect so the viewer can still look at the work on the commercial side and know that I made that photograph. I think as you progress in your career photo editors and creative directors start to trust you and your voice more and want to see that come out in the assignment. So even though I approach the two differently they do inform and inspire each other.

MK: What is the one thing you wish you knew when you started making photographs?

RT: I wish I had a better understanding around the responsibility and power I hold with my photography. Having a better grasp of that at a younger age I think would have helped developed my photography and made it stronger.

MK: What’s next for the photography of Rashod Taylor? I see a big future for you and wonder what your upcoming plans might be. May I also, at this time, say that others need to take a serious look at how and why and what you are photographing. Exhibition? Book? Something else?

RT: I want to keep focus on making the work and also promote and amplify the voices of other BIPOC artists to the forefront with opportunities and projects that I come across. For me getting my projects out there in different forms is what I will be striving for. A book for Little Black Boy is one of the longer-term goals and I would love to show in more museums and galleries. As of late, I have been taking on more commercial and editorial work which I enjoy as it gives me the opportunity to share stories and ideas that interest me. Outside of that, I am prepping for exhibitions, lectures, and workshops. I appreciate this opportunity Michael and thank you for having me!

You can find more of Rashod's work on his website here.

*This interview originally posted in its entirety at Analog Forever Magazine, October 18, 2020, here.

All photographs, ©Rashod Taylor