Jaime Aelavanthara

In what is now a slightly updated interview I had done for Analog Forever Magazine, I have the opportunity here again to highlight a photographic artist and educator that has inspired me and others for many years. Jaime Aelavanthara’s work and process have fascinated me for some time, and I felt the need to spread the word a bit more about her images and thoughts on the photographic arts.

Her work is at once profoundly magical and illustrative of the American South. The concepts and scenes she weaves through the cyanotype process are something to get lost in, and if you are not already familiar with her photography, now is the time. I find the warmth and textural feel of her work comforting, even when the content of an image might seem otherwise.

So I will do things a little differently with the layout this time and pepper her photographs from her body of work, Untamed, throughout, and then add a slideshow gallery with work from Where the Roots Rise. These are not her newest photographs, but I feel like they are significant collections that are great jumping-off points for getting more into her aesthetic as an image-maker and educator of amazing worth.

Jaime Aelavanthara is someone to keep your eye on as the years continue, as it is quite clear that her work and her words of wisdom come with great value. I hope you fall in love with these images as I have. They will stay with you forever.

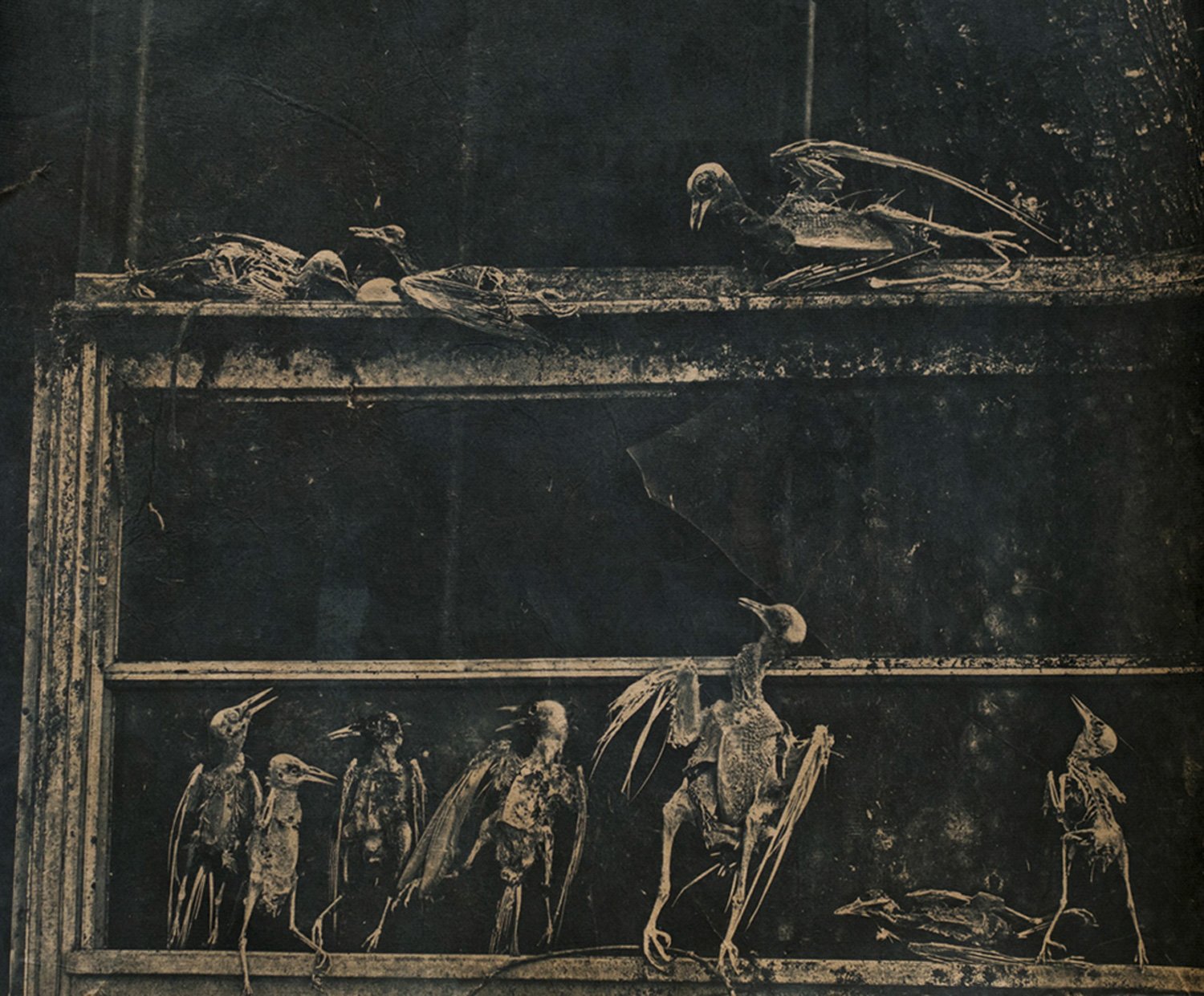

Becoming Fossil, from Untamed

Bio -

Jaime (Johnson) Aelavanthara grew up in the woods of Mississippi where whippoorwills, coyotes, and other wild animals outside her window became her daily melody. Jaime received her B.F.A. from the University of Mississippi in Imaging Arts & completed her M.F.A. in Photography at Louisiana Tech University in 2014.

Currently an Assistant Professor of Art at the University of Tampa department of Art + Design, her work explores themes of the human condition and an interconnectedness with nature. She has actively exhibited nationally and internationally in venues such as the Mississippi Museum of Art, SEITES Gallery, Canada, and the Ogden Museum of Southern Art. Her work has been used as cover art for literary works including The Virginia State Colony for Epileptics and Feebleminded (Persea Books, NY), and Venus in Furs (Roads Publishing, Dublin). Most recently, Aelavanthara won SOHO Photo Gallery’s 2017 International Portfolio competition and was awarded a solo exhibition at SOHO Photo Gallery, NY.

Jaime Aelavanthara has been recognized as a finalist in 2014 and 2015 for the Clarence John Laughlin Award, which recognizes photographers who utilize the medium of photography for creative expression. In 2015, Aelavanthara won the Grand Prize in Maine Media Workshops’ international competition Character: Portraits and Stories that Reveal the Human Condition. Aelavanthara's work has received past funding through a visual arts fellowship award from the Mississippi Arts Commission in 2016.

Her work is in public and private collections including the Mississippi Museum of Art in Jackson, the University of Arkansas in Little Rock, and the International House Hotel in New Orleans.

Interview -

Michael Kirchoff: Thank you for joining me in this interview, Jaime. I’ve admired your art-making for many years and have looked forward to learning more about you and your creative process. Can you give us some background on what got you started in the visual arts in the first place?

Jaime Aelavanthara: Before photography, I was constantly reading and being transported to other worlds through the written word. I found a similar sense of discovery in photography when my parents gifted me a camera at age 16. Photography became a huge creative outlet when I enrolled in a boarding high school away from home, at the Mississippi School for Math and Science. I enjoyed making science posters and lab reports visually appealing, and relished English and art courses. I spent summers off from high school photographing wildlife around the backyard, and the constant pursuit of photography led me to declare a Graphic Design major in college, though that didn’t last long. During my first official photography course, my professor Brooke White opened up an entire new world of photography for me, especially when it came to the darkroom. I soon declared a BFA in Imaging Arts (Photography and Video) and the rest is history! I never planned for a degree in the arts, much less, an MFA directly afterwards, but I felt there was more to learn.

MK: What is it that you get out of making art? Is there an overriding theme in your work that you feel best represents you as an artist?

JA: I enjoy when seemingly different phenomena can be related by an obscure connection, and how photography allows viewing of the world from unexpected, yet enlightening angles. For example, how a cicada wing resembles a fingernail. The process of artmaking definitely makes life more meaningful, and the relationship to my surroundings richer. I’m able to embrace a sense of childlike curiosity and wonder in the act of everyday observations. During the pandemic, after an initial hiatus from creating, I began channeling the stress into the creative process again, making photos without pressure on whether anything would come from the backyard photoshoots or not. Regarding themes, I constantly think about how we are all connected in this world, and what unites us, and to me, that is the shared human condition. Whether I’ve been in Mississippi, Louisiana, or, currently, Florida the past 3 years, all my work seeks a connection to my surrounding natural environment.

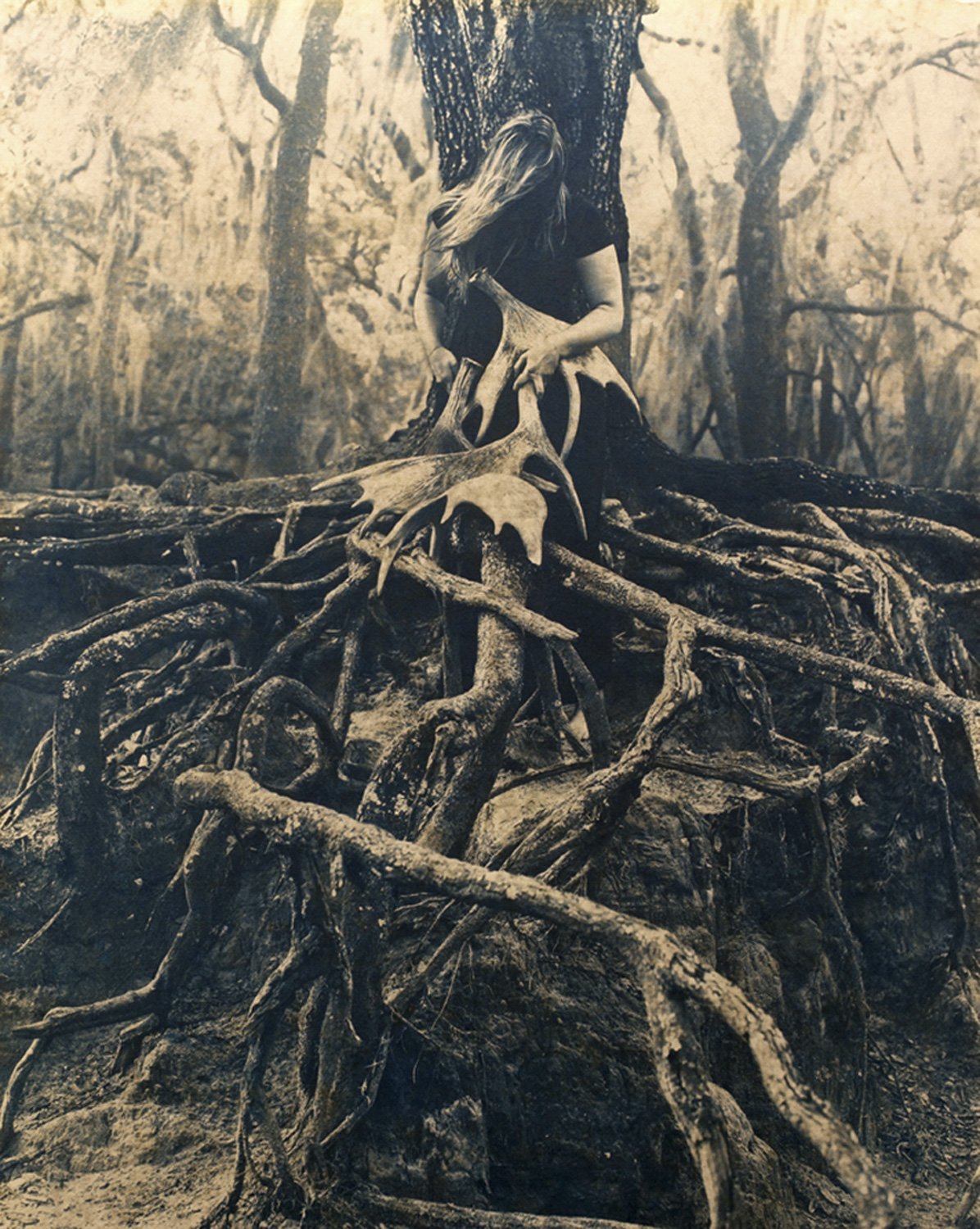

Bone Dress, from Untamed

Animal Tracking, from Untamed

Bag Worm Nest, from Untamed

Fallen, from Untamed

Feral Woman, from Untamed

MK: While you do partake in many different ways of making photographs, it appears that the cyanotype process, in particular, supports a great deal of your art. What was it that drew you to this process as a way of giving texture and tone to your imagery?

JA: During my MFA, I revisited cyanotype as a means to proof images, as the process is inexpensive and I was pursuing non-digital means of outputting my work. I didn’t expect anything to come from it, but I also began trying different papers, and that’s how I came upon a texture and tone combination that struck me and what began as a “proofing process,” turned into a serious pursuit. I was testing Japanese Kitikata paper, which fell apart without sizing. When I brushed gelatin sizing onto the absorbent paper over a sheet of plexi, it created wrinkles into the paper that would essentially harden in place. I’d peel the paper off from the plexi after it dried, and see a sheen from the gelatin remaining on the backside which created strength and allowed me to process the handmade paper without falling apart. I later accidentally left a print staining in a tea bath overnight, and the next day it appeared mostly tanned with some remaining navy tones. All of this exploration led to a magical combination of earthy tones and textured paper, that was later likened to “tanned animal hides.” As you know, each paper and how long you tone something, etc, all renders a unique result. I found an interesting combination in the materials that matched my vision on how I wanted the viewer to experience the prints in the “Untamed” series.

MK: Since we are on the subject of cyanotype, do you have any suggestions or advice for those willing to explore the process for themselves?

JA: If you have the option to take a workshop or learn from someone rather than diving in on your own, that’s a plus! Otherwise, alternative process photography groups online, textbooks, and video resources are plentiful. You don’t have to have a lot of equipment to get started, and there’s more than one way to do anything. It is good to think and consider what you are doing and why, but you don’t have to have all the answers on “why cyanotype” to get started, either. There are new things being explored with the process all the time, so if it’s your passion, stick with it.

MK: So much of your work seems to identify you and your aesthetic as a product of the American South, most especially in an earlier collection, Untamed. Was this something that came out in you during the artistic process, or is it something that you felt needed to be portrayed more intentionally?

JA: My experiences growing up in Mississippi are certainly embedded into who I am and the work I create; the connection in my work came naturally. Reflection during the writing process is definitely a moment when I directly embraced the sense of place when contextualizing the work. The topic of the American South is multi-faceted, and I was not particularly thinking about how I fit into the narrative of Mississippi, but just before I moved to Florida, I was honored to have a few cyanotype works acquired in the permanent collection at the Mississippi Museum of Art, and one on view in the exhibit New Symphony of Time that explores many aspects of Mississippi’s narrative—including themes of “shared humanity and the natural environment.”

Mask, from Untamed

Growth, from Untamed

Rebirth, from Untamed

Release, from Untamed

Snake, from Untamed

MK: While the majority of your work looks to be a solitary process, you have recently engaged in more collaborative endeavor with a newer collection, Blueprint/Redbloom. Can you tell us a little of how this came about and why the change this time around?

JA: When you meet that person that speaks your language, who opens the doors of possibilities on what you can do in a collaboration, that is a magical moment. This happened when I met an incredible creative force, Amanda Sieradzki: dancer, educator, writer, and mastermind of Poetica Dance who I am delighted to call a friend. Amanda and I both teach at the University of Tampa. We bounced ideas off for a piece to submit to Skyway 2020, a celebration of artistic practices in the Tampa Bay region. This brought us together to collaborate on an idea that would combine areas of visual art and dance to address topics on the red tide and algae blooms that affected the region. We began making cyanotypes on location in Florida, using collected beach water, choreographed movement, and the impression of beach detritus onto cyanotype murals. The project was postponed due to the pandemic but we are still in touch on future possibilities to combine forces.

MK: Honestly, the more I examine the different bodies of work you show on your website, the more I realize that you have no fear of experimenting and branching out into different ways of making images. While analog processes are quite prevalent, I do see that using digital technology and creating motion-based work are a part of your artistic life, not to mention sometimes a blending of all of these methods. Is this intentional, or are you simply a curious person with a need to create without boundaries?

JA: I certainly enjoy a combination of both digital and analog methods. It is exciting to think about technology we have at our fingertips today, and how this can merge traditional and new media. As an educator, there’s a lot of curiosity on my end when it comes to trying new things, to be able to share new processes in the classroom. I definitely feel like I could do more branching out, though I am opening up more lately when it comes to sharing newer work on my website, rather than holding onto images for long amounts of time before releasing them.

MK: In addition to your fine art photography, as you mention, you are an educator serving as the Assistant Professor of Art at the University of Tampa, in Florida. I also notice that in doing so you give voice to your students and their work on your own website, which is something I have not seen before to this degree. It seems clear to me that this is a large part of who you are as a person and as a photographic artist. Why this connection to nurturing others with your knowledge, and do you find that their work also informs your own?

JA: It is incredibly rewarding to teach in the university setting, as I think about how my own path in the arts flourished and started in this same environment. Teaching students, who are typically fearless to try new things, prompts me to remain curious and inquisitive in my own work, and that in turn, feeds into my ability to continuing learning new things to be able to share in the classroom. Regarding student work on my website, it is rewarding to take the time to archive what my students achieved, even if for my own reflection in teaching. Often, it’s to evaluate highlights of the academic year when students participated in something unique, such as a self quarantine/ pandemic online exhibition. It is a small means to support student voices, to share their work across social media, and certainly, with future students. It allows me to keep a record of meaningful work they are creating during this place and time, hopefully something to look back on for years to come and to continue building upon.

Spine, from Untamed

Swarm, from Untamed

Brevity, from Untamed

Ribs, from Untamed

Rest, from Untamed

MK: I have a few more general questions about how and why you make photographs to hopefully get into your head a little more. Does a body of work ever begin to form strictly through the editing process? Have you ever changed the direction of a body of work midstream?

JA: Most of the projects on my website are longer term, so I haven’t been one to change a direction of work midstream. However, the editing process did recently begin to form a new direction of recent images Palace of Leaves, made in the past few months of the pandemic. I looked at work made and pulled some of the images into a small grouping on my website. Being able to look at the works in this way definitely helped me formulate a combination of images and ideas to continue working with. Although its fresh off the press, finally organizing and seeing what I have been doing, I feel, has helped me form a new series through the editing process.

MK: Do you find it better to construct your images in a mindful way or work more intuitively?

JA: Overall I’m more intuitive, but I embrace a bit of “planned serendipity.” My strongest works aren’t often the specific ideas I set out to create but a combination of planned moments paired with chance. Before I go out to photograph, I usually have loose parameters—perhaps a location, or prop in mind, and then, I see what happens. I can set myself up for the right time of day or an interesting place, and perhaps a storm rolls in and adds more drama. Or, an interesting location got me out the door, only to stumble across something else entirely along the way.

MK: How do you know if you’re ever really done with a specific body of work? Do you ever go back to revisit images or collections to improve upon what you felt was previously finished?

JA: For my Untamed series, which was the culmination of my MFA exhibition at Louisiana Tech University, I continued adding to this series three years after the MFA program, so the project spans 6 years. So, while it seemed “finished” in 2014, I had to listen to my intuition that it was okay to continue adding to the project because I was still interested in it and making work in that vein. There wasn’t a hardline of “this is finished” for me, until I moved to Florida 3 years ago, and I knew I was finally at a transition period. I began a new series of cyanotypes, Where the Roots Rise, as a new chapter of cyanotype work, so to speak. This work still flows together with the previous Untamed series and both have been exhibited together, so I could absolutely see re-editing of collections, or even a merging of images together as possibilities down the line. Maybe the chaos of 2020 generated a recent change, but I’m open to letting myself move on from the cyanotypes and put images out into the world without feeling tied down and like I need to have it all figured out to share new work. I recently began to share some color pieces that are very much in progress. There’s a small thread to cyanotype as I started making gum bichromates over cyanotype prints with them, but I also decided to release straight digital versions, though the images will likely become translated into gum bichromates.

Where the Roots Rise:

MK: Do you have any other creative pursuits, or has photography become the one obsession that always takes precedence?

JA: I would say it is photography all the way, and perhaps video may circle back around again someday, which was an early part of my education. Gardening has taken a larger presence in my life (and feeds itself into my work!) My husband and I planted 20+ trees on our property leading into 2020. I have hopes to see them grow and for the trees to become part of continued photographic pursuits in the backyard.

MK: What is the one thing you wish you knew when you started making photographs?

JA: I am thankful that I overall learned the right lessons at the right times. For example, my only notion of a field in photography growing up was working for National Geographic. Obviously, there are so many other pursuits than that. I also recall being nervous contemplating the future very early on, but something told me I had to pursue what I was passionate about, and the rest would work itself out.

MK: What might we see coming from you in the future? Are there any exhibitions, books, projects, etc., that we will have the pleasure of experiencing?

JA: Pending pandemic disruption, this Spring I’ll have cyanotypes reproduced for viewing in Your Body Belongs to You, co-curated by Karen Harvey and Marisol Mendez at an outdoor exhibition site at the centre of St Gilles Croix de Vie, France.

I have cyanotype works (toned using Avocado leaves) published in Annette Golaz’s groundbreaking new textbook on tri-color cyanotypes in the Routledge series, entitled Toning Blueprints Naturally, released 2021.

Locally, I’m part of 65 Years in the Making, at The University of Tampa’s new Ferman Center for the Arts until Spring 2022. The exhibit spans all mediums with artwork by 27 alumni and faculty artists. This is a special exhibit highlighting the collaborative nature between students and faculty that occurs in the studio classroom environment, celebrating the artistic and professional mentorships at the center of the UT visual arts community.

What I'm working on currently: Blueprint/ Redbloom in collaboration with Amanda Sieradzki debuted in Skyway 2021 at the Tampa Museum of Art. The red tide algae blooms impacting gulf coast regions is a topic I look forward to researching and expanding upon in work to come for 2022.

*This interview originally posted in its entirety at Analog Forever Magazine, January 24, 2021, here.

You can find more of Jaime’s work on her website here.

All photographs, ©Jamie Aelavanthara